VB·3.1

| Inscription | |

|---|---|

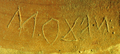

| Reading in transliteration: | latumarui : sapsutai : pe : uinom : natom |

| Reading in original script: | |

| Variant reading: | naxom naśom |

|

| |

| Object: | VB·3 Ornavasso (bottle) (Inscriptions: VB·3.1, VB·3.2, VB·3.3, VB·3.4, VB·3.5) |

| Position: | shoulder, outside |

| Orientation: | 0° |

| Direction of writing: | sinistroverse |

| Script: | North Italic script (Lepontic alphabet) |

| adapted to: | Latin script |

| Letter height: | 0.4–1 cm0.157 in <br />0.394 in <br /> |

| Number of letters: | 29 |

| Number of words: | 5 |

| Number of lines: | 1 |

| Workmanship: | scratched after firing |

| Condition: | complete |

|

| |

| Archaeological culture: | La Tène D [from object] |

| Date of inscription: | first half of 1st c. BC [from object] |

|

| |

| Type: | dedicatory |

| Language: | Celtic |

| Meaning: | 'to/for Latumaros and Sapsuta [something or other]' |

|

| |

| Alternative sigla: | Whatmough 1933 (PID): 304 Tibiletti Bruno 1981: 10 Solinas 1995: 128 1 Morandi 2004: 48 A |

|

| |

| Sources: | Morandi 2004: 550–552 no. 48 A |

Images

|

| ||||

Commentary

First published in Bianchetti 1895: 69 (no. 20). Examined for LexLep on 20th April 2024.

Images in Lejeune 1987: pl. XIII (photo = Solinas 1995: tav. LXIXb) and 498, fig. 2 (drawing), Piana Agostinetti 1972: tav. XXXI.12 (drawing), Graue 1974: Taf. 30.3 (drawing), Caramella & De Giuli 1993: tav. LXXVII.2 (drawing), Solinas 1995: tav. LXXc (photo), Morandi 1999: pl. IX.1 (photo) = Morandi 2004: tav. X.48), Morandi 2004: 566, fig. 12.48 (drawing).

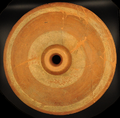

By far the longest inscription of five on the shoulder of the flask, the "Latumaros"-inscription is written above the outer of the two white bands (length ca. 16 cm). It is almost completely preserved on a single fragment, bar the first two letters; the break runs diagonally through/along one of the hastae of ![]() . An asterisk-like symbol is incised right above the bend of the flask's wall about 1 cm before the beginning of the inscription. The letters are neat and well legible, but there is debate concerning the identification of some of them.

. An asterisk-like symbol is incised right above the bend of the flask's wall about 1 cm before the beginning of the inscription. The letters are neat and well legible, but there is debate concerning the identification of some of them.

Letters no. 5, 14 and 18 have (more or less accurately) the shape ![]() , which was identified as mu – a Latinised variant – already by Bianchetti and by most later scholars. Letter no. 17 is a St Andrew's cross with a horizontal line directly underneath it, roughly connecting the two strokes of the cross. Bianchetti included this stroke in his rendering of the inscription and transliterated it with s. He was followed by Lattes 1896, who interpreted the letter as a variant of san

, which was identified as mu – a Latinised variant – already by Bianchetti and by most later scholars. Letter no. 17 is a St Andrew's cross with a horizontal line directly underneath it, roughly connecting the two strokes of the cross. Bianchetti included this stroke in his rendering of the inscription and transliterated it with s. He was followed by Lattes 1896, who interpreted the letter as a variant of san ![]() for [χs] as in Voltino saśadis, and naśom /naχsom/ as 'Naxian' to go with putative uinom 'wine'. Lattes compared the ending of latumarui to that on the pala-stelae and (taking it for a genitive according to the wisdom of the day) translated 'Naxian wine of Latumaros and Sapsutaipis'. The segmentation of sapsutaipe into another dative sapsutai and the enclitic conjunction -pe 'and Sapsuta' is due to, independently, Torp 1897: 4 and Kretschmer 1905. The inscription featured prominently in the genitive vs. dative debate, see Hirt 1905–1907: 564 f. and 1917: 210 f. as well as Danielsson 1909: 17 f., who interpreted the text as a gift inscription (but doubted the Naxian wine). Subsequently, the basic structure of the text, with Latumaros and Sapsuta as the recipients of something referred to by the last two words of the text, has been generally accepted, but the interpretations vary greatly in detail. Rhŷs and Whatmough agreed on 'for Latumaros and Sapsuta Naxian wine', though with different approaches to the last word: Rhŷs 1913: 63–67, no. 20 (also 1914: 25 f.) achieved the same interpretation as Lattes by reading letter 17 as Latin

for [χs] as in Voltino saśadis, and naśom /naχsom/ as 'Naxian' to go with putative uinom 'wine'. Lattes compared the ending of latumarui to that on the pala-stelae and (taking it for a genitive according to the wisdom of the day) translated 'Naxian wine of Latumaros and Sapsutaipis'. The segmentation of sapsutaipe into another dative sapsutai and the enclitic conjunction -pe 'and Sapsuta' is due to, independently, Torp 1897: 4 and Kretschmer 1905. The inscription featured prominently in the genitive vs. dative debate, see Hirt 1905–1907: 564 f. and 1917: 210 f. as well as Danielsson 1909: 17 f., who interpreted the text as a gift inscription (but doubted the Naxian wine). Subsequently, the basic structure of the text, with Latumaros and Sapsuta as the recipients of something referred to by the last two words of the text, has been generally accepted, but the interpretations vary greatly in detail. Rhŷs and Whatmough agreed on 'for Latumaros and Sapsuta Naxian wine', though with different approaches to the last word: Rhŷs 1913: 63–67, no. 20 (also 1914: 25 f.) achieved the same interpretation as Lattes by reading letter 17 as Latin ![]() with a diacritic understroke

with a diacritic understroke ![]() to distinguish it from Lepontic

to distinguish it from Lepontic ![]() , while Whatmough PID: 111–113, no. 304 (a), agreeing with Lattes, compared the form of putative san

, while Whatmough PID: 111–113, no. 304 (a), agreeing with Lattes, compared the form of putative san ![]() to that in MI·1 peśu – in the latter case, however, the form is created by an unintentional scratch under

to that in MI·1 peśu – in the latter case, however, the form is created by an unintentional scratch under ![]() (petu). That the stroke was unintentional also in the present inscription was proposed by Tibiletti Bruno 1978: 144–146 (also 1975: 55, 1981: 162–164, no. 10), who identified the letter as simple

(petu). That the stroke was unintentional also in the present inscription was proposed by Tibiletti Bruno 1978: 144–146 (also 1975: 55, 1981: 162–164, no. 10), who identified the letter as simple ![]() , but considered

, but considered ![]() in turn to be san (latuśarui, uinoś, natoś; in agreement Pellegrini 1983: 36 f.). Tibiletti's deviant reading entailed an interpretation of the two last words as acc.pl. forms uinoś natoś 'to L. and S. beautiful children'. Against Tibiletti Lejeune 1971: 74–76 (and in greater detail 1987: 495–504), who originally stuck with the Naxian wine, reading san for [χsi̯] or its outcome (naχsi̯om), but later (1987: 501) suggested an etymology with san for tau gallicum: uinom nađom 'never-depleting wine' (also Solinas 1995: 375, no. 128). Similarly to Lejeune's second solution, Birkhan 2005: 225–227 proposed an analysis with san for a dental cluster 'bound wine'. Morandi 2004 also rejected Tibiletti's reading of

in turn to be san (latuśarui, uinoś, natoś; in agreement Pellegrini 1983: 36 f.). Tibiletti's deviant reading entailed an interpretation of the two last words as acc.pl. forms uinoś natoś 'to L. and S. beautiful children'. Against Tibiletti Lejeune 1971: 74–76 (and in greater detail 1987: 495–504), who originally stuck with the Naxian wine, reading san for [χsi̯] or its outcome (naχsi̯om), but later (1987: 501) suggested an etymology with san for tau gallicum: uinom nađom 'never-depleting wine' (also Solinas 1995: 375, no. 128). Similarly to Lejeune's second solution, Birkhan 2005: 225–227 proposed an analysis with san for a dental cluster 'bound wine'. Morandi 2004 also rejected Tibiletti's reading of ![]() , but tentatively preferred natom over readings which include the stroke below the letter. Stifter 2011b: 176, n. 22 (also 2024: 135) suggested, like Rhŷs, that the stroke may be a diacritic to a Latin xenograph

, but tentatively preferred natom over readings which include the stroke below the letter. Stifter 2011b: 176, n. 22 (also 2024: 135) suggested, like Rhŷs, that the stroke may be a diacritic to a Latin xenograph ![]() , or, alternatively, iota written in ligature. Whether uinom natom is a nominative ('... for L. and S.') or accusative (elliptical '[X gave] ... to L. and S.') phrase is technically uncertain, but it is usually considered to be the subject (explictly Rhŷs 1913: 66, 1914: 25 f., Lejeune 1971: 75, Stifter 2020: 34; accusative: Solinas 1995: 375) – this is of course only possible if the phrase is neuter, as per the 'Naxian wine' interpretation, rather than masculine. See the word pages for details on the various linguistic analyses.

, or, alternatively, iota written in ligature. Whether uinom natom is a nominative ('... for L. and S.') or accusative (elliptical '[X gave] ... to L. and S.') phrase is technically uncertain, but it is usually considered to be the subject (explictly Rhŷs 1913: 66, 1914: 25 f., Lejeune 1971: 75, Stifter 2020: 34; accusative: Solinas 1995: 375) – this is of course only possible if the phrase is neuter, as per the 'Naxian wine' interpretation, rather than masculine. See the word pages for details on the various linguistic analyses.

Tibiletti's assertion that ![]() had to be san, because Lepontic mu

had to be san, because Lepontic mu ![]() was attested in VB·3.2 according to her reading, can be dismissed; Latinised mu – also in combination with Lepontic nu – is well attested in late Lepontic inscriptions, e.g. VC·1.2, VB·1. The question of letter 17 is more difficult. The horizontal stroke is not obviously an unintentional mark – it matches the lines of the letters in thickness, and no evidently similar scratches can be seen elsewhere on the flask's surface. It does, however, appear to be slightly deeper than the lines of the St Andrew's cross, and its edges are somewhat less frayed. A different execution of the stroke could be accounted for by Rhŷs/Stifter's suggestion that it is a diacritic, as it may have been added belatedly. If the stroke is unintentional, the letter is evidently

was attested in VB·3.2 according to her reading, can be dismissed; Latinised mu – also in combination with Lepontic nu – is well attested in late Lepontic inscriptions, e.g. VC·1.2, VB·1. The question of letter 17 is more difficult. The horizontal stroke is not obviously an unintentional mark – it matches the lines of the letters in thickness, and no evidently similar scratches can be seen elsewhere on the flask's surface. It does, however, appear to be slightly deeper than the lines of the St Andrew's cross, and its edges are somewhat less frayed. A different execution of the stroke could be accounted for by Rhŷs/Stifter's suggestion that it is a diacritic, as it may have been added belatedly. If the stroke is unintentional, the letter is evidently ![]() . If it is intentional, the two epigraphical options – Latin ksi with a diacritic or with iota in ligature – are stated by Stifter. A comparable case to the former option may be found in VB·24, where Latin ksi appears as

. If it is intentional, the two epigraphical options – Latin ksi with a diacritic or with iota in ligature – are stated by Stifter. A comparable case to the former option may be found in VB·24, where Latin ksi appears as ![]() , a form which seems to have been made up by the writer to avoid the homography with Lepontic

, a form which seems to have been made up by the writer to avoid the homography with Lepontic ![]() , but "iotised"

, but "iotised" ![]() is unparalleled to our knowledge; the understroke can also hardly be a forgotten iota, as the writer actually did forget the initial sigma of sapsutai and fit it in expertly between the separator and alpha – had he left out iota, he could surely have done the same. The reading of a letter san

is unparalleled to our knowledge; the understroke can also hardly be a forgotten iota, as the writer actually did forget the initial sigma of sapsutai and fit it in expertly between the separator and alpha – had he left out iota, he could surely have done the same. The reading of a letter san ![]() , finally, is highly unlikely, as such a form is not attested elsewhere. As the issue cannot be resolved from an epigraphic perspective, we turn to linguistic considerations.

, finally, is highly unlikely, as such a form is not attested elsewhere. As the issue cannot be resolved from an epigraphic perspective, we turn to linguistic considerations.

That Lattes' naśom 'Naxian' lacked a suffix was already noted by Kretschmer 1905: 99–101, no. 20. The same is true of Rhŷs' naxom, which the author referred to as "reduced". The only readings which introduce the palatal element necessary for the Naxian wine are Stifter's unlikely ligature and Lejeune's san [χsi̯], which is weakened both by the implausibility of a letter san ![]() and by the fact that the form should be not naχsi̯om, but naχsii̯om. We may thus have to abandon Lattes' Naxian wine, which has proved popular not least because of its intriguing implications about trade relationships between the Greek and Cisalpine Celtic world, and the position of Naxos as one of the alleged birthplaces of Dionysos. In this case the assumption of a xenograph

and by the fact that the form should be not naχsi̯om, but naχsii̯om. We may thus have to abandon Lattes' Naxian wine, which has proved popular not least because of its intriguing implications about trade relationships between the Greek and Cisalpine Celtic world, and the position of Naxos as one of the alleged birthplaces of Dionysos. In this case the assumption of a xenograph ![]() becomes superfluous. The dubiousness of the san-reading also compromises the formally superior analyses of naśom by Lejeune 1987 and Birkhan. While Lejeune's 'never-depleting wine' is semantically very attractive for a gift inscription, Birkhan's nađom 'bound' is not convincing to me – Birkhan explains the phrase as referring to wine made from vines which are tied to a structure rather than left to grow along the ground, but it is the vines which are tied (vitis iugata or canteriata), not the wine. The most viable option may in fact be simple Lepontic

becomes superfluous. The dubiousness of the san-reading also compromises the formally superior analyses of naśom by Lejeune 1987 and Birkhan. While Lejeune's 'never-depleting wine' is semantically very attractive for a gift inscription, Birkhan's nađom 'bound' is not convincing to me – Birkhan explains the phrase as referring to wine made from vines which are tied to a structure rather than left to grow along the ground, but it is the vines which are tied (vitis iugata or canteriata), not the wine. The most viable option may in fact be simple Lepontic ![]() disturbed by an unintentional scratch, as in MI·1. The relinquishment of Naxos draws into question the identification of uinom as 'wine', since in principle a reading u̯indom, as per Tibiletti Bruno 1978: 145, is equally possible. An interpretation of uinom as an adjective 'fair' uel sim. is rendered problematic, however, by its position before natom, as the adjective should be expected to follow the noun.

disturbed by an unintentional scratch, as in MI·1. The relinquishment of Naxos draws into question the identification of uinom as 'wine', since in principle a reading u̯indom, as per Tibiletti Bruno 1978: 145, is equally possible. An interpretation of uinom as an adjective 'fair' uel sim. is rendered problematic, however, by its position before natom, as the adjective should be expected to follow the noun.

Lattes assumed that the text was inscribed for a libation ritual during the burial, but, as pointed out by Morandi 1999: 172, no. 17 (also 2004: 550–552, no. 48 A), only one person is buried in the grave, so that the inscription was probably buried with one of the two original recipients of the flask. The inscription thus represents one of the best pieces of evidence for a secular gift inscription in the corpus, and an example for an inscription on a piece of grave furniture which is unconnected to the burial. Pisani 1964: 286 f., no. 124 (a) thought that the vase was a marriage gift; Morandi 1999 (ibid.) suggested that the four short inscriptions VB·3.2, VB·3.3, VB·3.4 and VB·3.5 are the names of the gift givers. Lejeune 1971: 74–76 drew attention to the syntactical hierarchy of separators, which separate the nominative and accusative phrases (four dots), the two lexical/onomastic elements within each phrase (three dots) and sapsutai from the enclitic (two dots); in 1987: 495–504, he suggested that the text may be metrical (also Stifter 2011b: 175 f., Stifter 2020: 34). What exactly was given to (or wished upon) Latumaros and Sapsuta remains uncertain.

Lejeune 1971: 74–76 highlighted final -m as a Lepontic feature (cf. VC·1.2). With regard to the various clear and potential elements of Latin influence in the inscription (Latin mu, uinom, natom), it could instead be a Latinisation feature; however, the inscription is one of only three late Lepontic documents which attest the archaic dative endings -ūi̯/-āi̯ (cf. NO·18, BS·2), which renders the presence of the archaic sound form of the neuter nominative/accusative quite natural.

See also Giussani 1902: 55–57, Jacobsohn 1927: 31, no. 192, Terracini 1927: 148 f., PID: 554 f., Piana Agostinetti 1972: 272, no. 12, Lambert 1994: 21, Morandi 1999b: 308–312, no. 4, Tori 2015.

Bibliography

| Bianchetti 1895 | Enrico Bianchetti, I sepolcreti di Ornavasso [= Atti della Società di Archeologia e Belle Arti della provincia di Torino 6], Torino: Paravia 1895. |

|---|---|

| Birkhan 2005 | Helmut Birkhan, "UINOM NAŚOM", in: Franziska Beutler, Wolfgang Hameter (Eds.), "Eine ganz normale Inschrift" ... Vnd ähnLiches zVm GebVrtstag von Ekkehard Weber. Festschrift zum 30. April 2005 [= Althistorisch-Epigraphische Studien 5], Wien: Eigenverlag der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Archäologie 2005, 223-228. |

| Caramella & De Giuli 1993 | Pierangelo Caramella, Alberto De Giuli, Archeologia dell'Alto Novarese, Mergozzo: Antiquarium Mergozzo 1993. |

| Danielsson 1909 | Olof August Danielsson, Zu den venetischen und lepontischen Inschriften [= Skrifter utgivna av Kungliga Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala 13.1], Uppsala – Leipzig: 1909. |